The advent of the Internet and of mass digitization of research information processes brought about among many other things the ability to harvest, sometimes implicitly, a wealth of human behavioral, biological, economic, political, or social data. The emergence of social media further amplified this trend, as each post, like, share or comment can be turned into analyzable data. The sequencing of the human genome and the inventory of many basic molecular processes in the human body have further expanded the universe of information. It is estimated that 90 % of all existing data was generated in the last few years (Wall 2014). Furthermore, data typically arrives as a deluge, not as a trickle. In the previous decades, social research was limited to samples of hundreds of thousands of cases. Now, datasets include millions of records. Seen from this lens, data has acquired the attribute “big.” This is, however, not only a quantitative attribute, but a qualitative one (Macy 2015). Big data refers often to populations and takes the form of complete counts. It is, at the same time, captured not only as attributes, but as relationships (Harris 2013). Sieving through the census-like inventories with high speed and highly efficient computing algorithms has made possible new discoveries in genetic and clinical medical research or in social scientific understanding of diffusion processes (Christakis and Fowler 2009).

Data collection on such a massive scale involving millions of individuals and data points was many times done through automated, technological means that left some human ethical concerns aside to be discussed after the fact. Such a situation is fraught with dangers, including major harm to the individuals observed. Their right to privacy, free expression, autonomy and their trust in the scientific establishment

J. Collmann (&)

Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA e-mail: [email protected]

S.A. Matei (&)

Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA e-mail: [email protected]

© Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2016 1 J. Collmann and S.A. Matei (eds.), Ethical Reasoning in Big Data,

Computational Social Sciences, DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-28422-4_1

2 J. Collmann and S.A. Matei

or in government can be put in serious danger. Creating a framework for ethical reasoning that can be employed before the research process starts, thus, becomes an obvious priority for the research community.

This book grows from a multidisciplinary, multi-organizational and multi-sector conversation about the privacy and ethical implications of research in human affairs using big data. Authors include a wide range of investigators, practitioners and stakeholders in big data about human beings who also routinely reflect on the privacy and ethical issues of this phenomenon. Together with other colleagues, all participated in a workshop entitled “Privacy in the Infosphere: an NSF-sponsored workshop on ethical analysis of big data”. The authors have several different per- spectives on big data but all express caution in rushing to judgment about its implications. Their diversity suggests the stakes at hand in big data, especially the stakes for scientific research and science as a legitimate institution in our society. Yet, perhaps, because of its implications for individual privacy and the spectacular revelations about various uses of big data by government and commercial orga- nizations, discussions about the ethics of big data have not remained solely the purview of specialists—the public takes an interest. Thus, the authors of this book write with their eyes and ears directed in multiple directions: toward their peers in scientific research, toward the government and philanthropic agencies who fund research, and toward the citizens of our society whose taxes underpin, and whose lives provide the information that constitutes the focus of much big data research.

We subtitled this book “an exploratory analysis” because we think that many ethical questions remain unanswered, indeed unasked, about big data research focused on human affairs. Our limited experience with big data in all its contem- porary forms urges caution and humility but not inaction. We are all actively engaged in big data research about human affairs in one way or another and think that ethical reasoning about big data issues as they emerge from scientific practice is likely to produce more useful results than speculation in the absence of experience. Yet, controversy exists about the form, extent, context and formality of reasoning about big data ethical issues.

For example, participants in our privacy workshop did not all agree on several issues, such as the connection between data provenance and privacy concerns or the mechanisms by which privacy procedures should be designed. The workshop occurred on April 15–16, 2015 in the Philodemic Room of Georgetown University, Washington, DC. The participants included an organizing committee, a multidis- ciplinary set of researchers who have received NSF funding for big data projects from the Education and Human Resources Directorate (EHR) and the Building Capability and Community in Big Data (BCC) program, and a distinguished panel of big data stakeholders from a range of disciplines, organizations and community sectors, a composition intended to capture diverse perspectives and encourage lively discussion. The organizing committee prepared and sent materials to all participants before the workshop to help create a common foundation for launching the discussion. The materials included a white paper, a case study template and an example case study. After reviews of the concepts of big data and of privacy, the white paper focused on a heuristic device (the Privacy Matrix) designed to assist big

Introduction 3

data investigators in identifying privacy issues with potential ethical implications in their work (Steinmann, Shuster, Collmann, Matei, Tractenberg, FitzGerald, Morgan, and Richardson 2015 and Steinmann, Matei and Collmann below). Four participants prepared case studies based on their own experience.

The diversity of backgrounds, experiences and organizational affiliation mani- fested itself in a diversity of perspectives on the interpretation of the case studies, the implications of big data research for privacy and ethical analysis and ideas about Data Management Plans as tools for protecting privacy and promoting ethical reflection in big data research. Some participants argued that, in contrast to gov- ernment or commercial uses of big data, big data research posed few new privacy or ethical issues and that existing mechanisms (including the existing guidance for NSF proposal Data Management Plans) sufficed to handle them. Adding new ethical concerns or human subject review questions might increase the bureaucratic overhead without enhancing the value of big data science. Other participants argued that big data research invites renewed reflection on privacy and ethical issues in scientific research. Although existing mechanisms might suffice in some cases, other cases such as those presented in the workshop challenge current practice and institutional procedures. In addition, some research communities such as computer scientists have begun work on big data about human subjects with little experience of the human subjects protection process or tradition. Until such time as the sci- entific community has developed more experience with big data research, indi- vidual scientists and their institutional research support groups should examine big data projects on a case-by-case basis using tools such as the Privacy Matrix (Steinmann, Shuster, Collmann, Matei, Tractenberg, FitzGerald, Morgan, and Richardson 2015 and Steinmann, Matei and Collmann below) or expanded Data Management Plan format (see Collmann, FitzGerald, Wu and Kupersmith below) to assist them in proactively anticipating issues while planning research and com- prehensively analyzing issues as they arise in the course of research. This diversity of opinion echoes the current controversy over the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking for Revisions to the Common Rule (see http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/ regulations/nprmhome.html).

Dedicated to the practice of ethical reasoning and reflection in action (see DiEuliis and Giordano, Tractenberg below), the authors in this book offer a range of observations, lessons learned, reasoning tools and suggestions for institutional practice to promote responsible big data research on human affairs. The need to cultivate and enlist the public’s trust in the ability of particular scientists and the institutions of science constitutes a major theme running throughout the book. When scandals develop about the misuse or breach in confidentiality of individually identifiable information in human subjects research, participants suffer various types of harm and science as an institution in our society sustains some loss of the public’s trust and sense of legitimacy. Above all, as Rainie describes in his chapter on the results of Pew surveys on privacy in America, members of the public expect to grant permission for researchers to gather, use, and secondarily reuse data about them, especially individually identifiable data such as biospecimens.

Waymo Data Scientist interview

04/04/2023

Waymo Data Scientist interview

04/04/2023

What is intelligent electronic device?

03/04/2023

What is intelligent electronic device?

03/04/2023

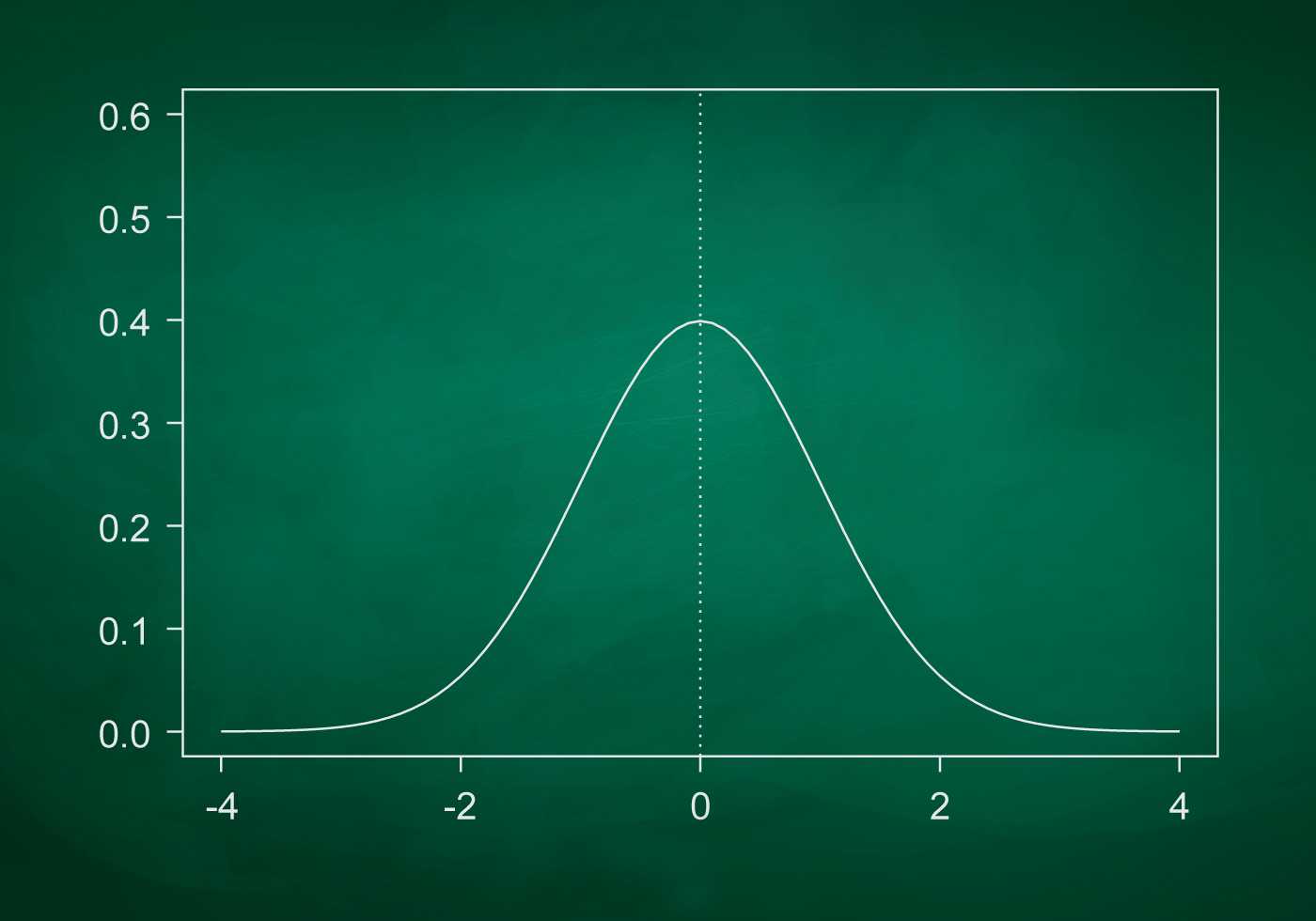

What is standard deviation definition

10/11/2022

What is standard deviation definition

10/11/2022

What is Power BI and how to use it

10/11/2022

What is Power BI and how to use it

10/11/2022